The term Global South was first coined and introduced into the lexicon of political terms and international relations by Carl Oglesby , an American author and New Left activist, in 1969. In an article he wrote for the Catholic magazine Commonwealth at the height of the Vietnam War, Oglesby analyzed the state of the world as follows: the countries of the Global North—the Northern Hemisphere—have converged and aligned to create an intolerable social order for the Global South.

Prior to Oglesby's definition, most Western analysts divided countries into three worlds:

• The First World: Consisting of the United States and its Western allies.

• The Second World: Composed of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc.

• The Third World: Made up of developing nations, most of which were non-aligned with either power bloc or had recently been liberated from the dominion of their colonial powers.

The term Third World was first introduced into global political literature in 1952 by the French demographer Alfred Sauvy . It was later popularized by Peter Worsley in 1964 with the publication of his book, The Third World: A Vital New Force in International Relations. In his book, Worsley argued that the Third World formed the backbone of the Non-Aligned Movement, which had been founded just three years earlier by a significant number of countries in response to the bipolar system of the Cold War era.

Although Worsley published his book with positive and benevolent intentions, the term became associated with countries suffering from poverty, misery, and instability. The Third World became synonymous with Banana Republics —often depicted humorously or satirically in Western media—countries governed by dictators, whose political and economic instability meant their economies were dependent on the export of natural resources (chiefly agricultural products), and whose ruling class ran the nation like a private commercial enterprise, with export profits serving solely the ruling elite. The American author William Sydney Porter (1862–1910), known as O. Henry, coined the term "Banana Republic" in 1904 to describe the fictional Republic of Anchuria in his book Cabbages and Kings.

In the 1970s, as countries of the South worked within the framework of the United Nations to establish a New International Economic Order (NIEO), the term Global South gained traction as a more respectful synonym for the Third World. The first step was taken on May 1, 1974, when the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 3201 (S-VI) concerning the NIEO, based on principles including the sovereign equality of states and interdependence. This NIEO was intended to:

1. Secure common interests and cooperation among states, irrespective of their economic and social system differences.

2. Redress the disparity in development levels and compensate for the harm resulting from injustice.

3. Eliminate the widening gap between developed and developing countries.

4. Ensure a continuous process of socio-economic development, peace, and justice for the present and future generations.

Despite the efforts made in the 70s, it was primarily the Brandt Report in 1980 that brought the concept of the Global South to true prominence and popular usage. This landmark document, written by an independent international commission led by Willy Brandt , the former Chancellor of West Germany, drew a distinction between countries with relatively higher per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—mostly concentrated in the Northern Hemisphere—and the poorer countries. Most of the latter group were located in the geographical South or below the Brandt Line. The Brandt Line was a hypothetical dividing line that started at the Rio Grande River (the border between Mexico and the United States) and reached the Gulf of Mexico, then extended across the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and large parts of Central Asia to the Pacific Ocean.

However, the Brandt Line did not align perfectly with geographical realities, as many countries counted among the poorer nations by per capita GDP and identified as the Global South are located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere. Conversely, wealthy nations like Australia and New Zealand are situated below the equator and in the Southern Hemisphere.

Regardless of the per capita GDP indicator, the common characteristics of the countries of the Global South generally include: a high level of poverty, a high level of income inequality, low life expectancy, and harsher living conditions compared to the Global North.

Following the collapse of the Communist bloc and the end of the Cold War, the term Third World gradually lost its popularity, both because the Second World no longer existed and because many countries found the term to be derogatory. The title "Third World" evoked a group of backward, socio-politically unstable nations mired in poverty. Compared to the Third World, the term Global South offered a more neutral and appealing label.

Following the establishment of the Group of 77 (G77), the term Global South increasingly found a new synonym. This coalition of post-colonial, developing countries united in 1964 to collectively defend their joint economic interests and increase their negotiating power at the United Nations. Today, 134 countries are members of the G77 and refer to themselves as the Global South. The UN has launched several international bodies and initiatives to address the needs and goals of this group of countries, including the United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation.

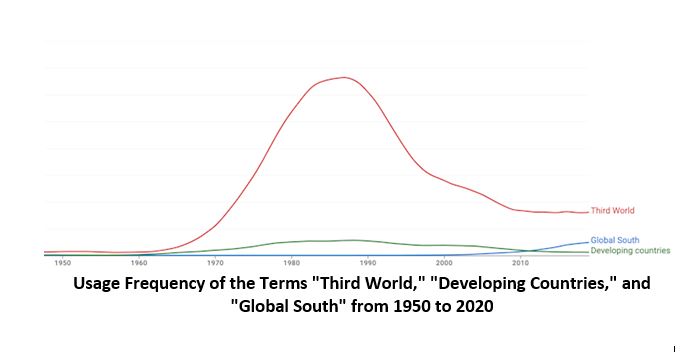

As the following chart illustrates, the use of the term Third World in international relations literature and international documents began to rise in the mid-1960s and peaked in 1990. Over these three decades, neither of the other two terms, "Developing Countries" or "Global South," was used in the literature to the extent of "Third World." Following the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc, the usage of "Third World" gradually declined. As the chart below shows, the use of the term Global South has been steadily increasing since early 2010.

Ambiguities Concerning the Global South

The question arises today: Is the term Global South, regardless of its historical background and usage, logical and meaningful? The most significant limitation of its application is clearly its conceptual incoherence. This title encompasses a bizarre collection of about 130 countries that are remarkably heterogeneous, spread across a vast geography covering Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Oceania, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and housing roughly two-thirds of the world’s population. This group includes states ranging from Barbados in the Caribbean, to Bhutan, Malawi, Malaysia, Pakistan, Peru, Senegal, and Syria. It also spans small countries like Benin, Fiji, and Oman, to major powers like Brazil, India, and Nigeria, which are now emerging powers and contenders for permanent seats on the UN Security Council.

Some members of the Global South may have overlapping interests on specific issues, but it remains unclear how much political weight and standing this vast Meta Group offers in global equations, especially given the sheer economic, political, and cultural diversity among its members. This ambiguity deepens when considering the unique national interests and preferences of each country within the group. In reality, using the term Global South risks reinforcing outdated, incorrect stereotypes and dualisms, thereby neglecting its genuine economic, political, and geopolitical diversity.

Among the other limitations of the Global South is that it ignores the remarkable growth of many of its members in recent decades. From an economic perspective, it seems illogical to group Malaysia, with a per capita income of $28,150 (based on Purchasing Power Parity or PPP), alongside Zambia, with a per capita income of $3,250 (PPP). Similarly, there is no economic rationale for grouping a country like Costa Rica, which is at the forefront of environmental protection and clean energy use, with an oil state like Nigeria, which remains reliant on fossil fuels.

The general and comprehensive title of the Global South also overlooks the diversity of political regimes and quality of governance among its members. The latest annual "Freedom in the World" survey by the NGO Freedom House , based on criteria for public access to political rights and civil liberties, shows that the scores of Global South countries vary widely: Sudan and Syria are at the lowest level of 1 (Not Free), while Uruguay is at the highest level of 96 (Free).

Furthermore, the title Global South offers no clear view of the geopolitical orientation of its members. The war in Ukraine exemplifies this. In the February 2022 UN General Assembly vote on a resolution demanding Russia’s immediate withdrawal from Ukrainian territory, the Global South split: over 60% of members voted in favor of the resolution, while nearly one-third of Global South member countries abstained. Global South members are also sharply divided on reforms to the UN Security Council; some favor increasing the number of permanent members (including from developing countries), while others are vehemently opposed. Overall, the Global South lacks a clear strategic orientation in global equations.

It should, however, be noted that political titles such as Third World, Developing, or Global South are not fixed labels; rather, they evolve in response to changing global realities, conceptual insights, and sensitivities. For instance, the long-standing distinction between so-called developed and developing countries was criticized for its implicit and explicit reliance on a linear progression of technology, as it classified countries based on their distance from or proximity to the Western model of technological advancement. For this reason, the World Bank announced in 2015 that it would gradually discontinue the use of the term "developing world," noting that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—which aim to guide global efforts to improve the human condition by 2030—apply to all countries, regardless of their income status.

The term Global South appears to have more staying power, at least for now. However, it is wise for analysts and policymakers to use this term with greater awareness and restraint than other labels and avoid sweeping, outdated generalizations.

One of the tragedies of the Cold War era was the United States' tendency to use the Third World as an indifferent terrain for zero-sum competition, rather than engaging them as sovereign actors with distinct identities, interests, and motivations. A similar dynamic is re-emerging as the global rivalry between China and the US heats up. To prevent a repetition of past mistakes, policymakers must be careful not to treat the Global South as a monolithic entity. Instead, they should formulate separate strategies for engaging with each member country, particularly the pivotal ones such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa, or Turkey.

Generally, and by way of policy prescription, governments should deeply examine their relationships with the many low- and middle-income countries that identify as members of the Global South. The key to managing relations with this group is understanding that the degree of solidarity and cohesion among each member of the Global South "family" is variable, and their actual preferences on various political issues differ widely. Furthermore, countries may label themselves members of this group for instrumental or rhetorical reasons, or for temporary, opportunistic gain.

Finally, while the appeal of the Global South brand to its proponents stems primarily from the vision it creates for achieving a more equitable and inclusive global economy or the promise of creating a multipolar international system, policymakers and academics must consider that these ambitions are not equally shared among all members. For many in this group, the imperatives of sustainable development and economic growth may hold greater importance than geopolitical issues and global order.

Alireza Ghizili, Senior Expert at the Center for Political and International Studies

(The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the IPIS)