The global balance of power is shifting from unipolar to multipolar, with influence distributed among multiple centers. One such center is India, the world’s most populous country. India’s policies shape South Asia and greatly impact global economic and geopolitical dynamics.

India’s foreign policy, particularly under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has been characterized by a doctrine of multi-alignment. This seeks to balance relations with major powers while prioritizing national interests and regional stability. India’s neutrality in the Russia–Ukraine War reflects its strategic autonomy and commitment to a multipolar world order, positioning it as a leader within the Global South.

The South Caucasus has recently become a region of interest for India. For much of independent India’s history, the region was part of the Soviet Union, and Indian foreign policy tends to view it through Moscow’s prism. After 1991, when the South Caucasus countries became independent, India increasingly saw the region as an area of interest, albeit with limited engagement.

The South Caucasus shares a border with Iran and was part of the Iranian empire until the early 19th century. Given the growing alliance between Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Pakistan, India favors engaging with the South Caucasus through Iran. Iran plays a crucial role on both geo-economic and geopolitical fronts, particularly in connectivity-related projects. As discussed in this analysis, these trade and infrastructure initiatives hold transformational potential for the South Caucasus. However, realizing this potential requires close cooperation between New Delhi and Tehran. Unfortunately, bilateral relations between these two civilizational partners remain constrained by US and Western-imposed sanctions on Iran. While the initial signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action raised hopes of easing these restrictions, the change in the US administration quickly dispelled such expectations.

As longstanding regional powers and rising geopolitical players in Eurasia, Iran, and India are keen to implement projects that enhance cross-regional connectivity within the Eurasian heartland. These include infrastructure initiatives such as the Chabahar Port and the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). However, recent geopolitical developments and consequent insecurities have stymied progress on these two projects.

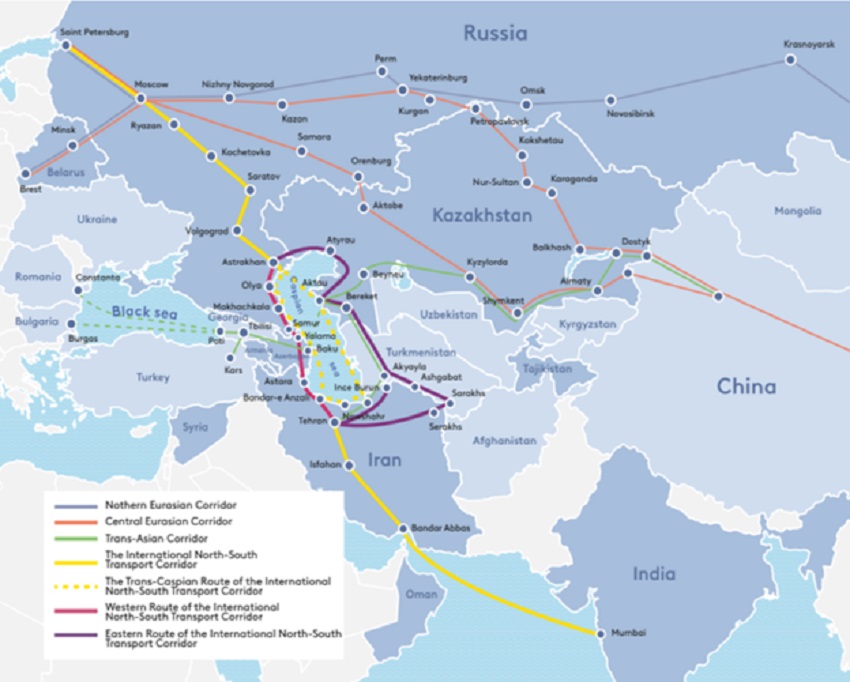

The INSTC is a key project for India’s connectivity with the Eurasian heartland, a resource-rich and sparsely populated region. It envisions three branches.[1] All three routes pass through Iran, with one passing through the South Caucasus. One of the key elements of these communication routes is Chabahar, a deep-sea port located on Iran’s southern coast with the potential to become one of the key links between the Indian Ocean and the European part of the Eurasian continent. The Chabahar Port is already one of the key links in the Iranian-proposed Persian Gulf–Black Sea Corridor, which envisions a direct link between Chabahar and the Georgian Black Sea coast through the territory of Armenia. This route largely coincides with the westernmost branch of the INSTC.

Reference: The map of Eurasia's transport routes, including the INSTC. Source: Eurasian Development Bank.

Within the existing framework of the Persian Gulf–Black Sea Corridor, a direct India–Iran–Armenia–Georgia–European Union link could be created. Thus, India and Iran’s interests in the South Caucasus coincide with unlocking the region’s transit potential.

Various trade routes already exist that connect Europe with Asia. However, recent global and regional instability threatens the viability of many routes, such as the Suez Canal or routes that go through Russia. Thus, there is an ongoing need to diversify connectivity routes within Eurasia. Turkey and Iran are strategically positioned to become the regional transit hub in the South Caucasus. Turkey’s current role is defined by East–West communication routes that connect Europe through Turkey with the Middle East and Central Asia. Iran is strategically positioned in North-South communications routes that link Russia with the Persian Gulf. By cooperating with India to develop the South Caucasus-based branch of the INSTC, which contains both East-West, and North–South elements, Iran can gain an advantage in becoming the key regional transit hub.

An important element of India’s emergence as a global power center is the development of its military-industrial complex. Between 2019 and 2023, India was the largest arms importer globally, with a 9.8% share of global imports. Its leading suppliers were Russia, France, the US, and Israel. Given the advanced development of its technological and defense industries, India is now among the world’s top 25 arms exporters. Its products —a combination of Western, Russian, and native technologies—are competitive in the global market given their high quality but low cost. India seeks to significantly increase its arms exports to reach appropriate economies of scale to countries that do not threaten India or its allies.

Armenia has emerged as one of the top purchasers of Indian arms, and this relationship has become an important entry point for India in the global arms export market. Amid Armenia’s conflict with Azerbaijan, supported by Turkey and Israel, and at a time when Russia could not meet its arms-supply commitments to Armenia due to its war in Ukraine, India fulfilled Yerevan’s urgent procurement needs for advanced weapons. India has agreed to supply more than $1.5 billion worth of arms, including Swathi weapon-locating radars, Pinaka multibarrel rocket launchers, anti-tank rockets, Trajan 155mm towed artillery, the Akash air defense system, towed and self-propelled howitzers, Ashwin ballistic missile interceptors, and various types of ammunition. These exports bolster India’s defense industry and strengthen the global awareness of Indian-made weapons, encouraging other countries to consider them viable options.

Strategically, India’s engagement with Armenia is a welcome development for Iran. After Azerbaijan, with the support of Turkey, Israel, and Pakistan, changed the regional power balance in its favor, India’s arms sales to Armenia may help restore this balance in the long term. Moreover, the trilateral military and military-technical cooperation between Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Pakistan, including joint military exercises and arms production, is a cause for concern for India, Armenia, and Iran.

Reducing the power imbalance in the South Caucasus will bring stability to the region, thus supporting Iran’s regional policy. Ankara and Baku have been promoting projects to change the region’s geopolitical landscape with the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” and the concept of “Western Azerbaijan.” These projects would not only significantly undermine Armenia but also block Iran’s alternative access routes to Russia and Europe. This would, in turn, force all three routes of the INSTC to pass through regions of Turkish influence, hampering the original purpose of diversifying, not concentrating, communications routes. Further, these Turkey-led initiatives, should they occur, would fit into Ankara’s recent drive to expand its influence beyond the confines of the former Ottoman Empire. In Central Asia, it has leveraged the Turkic ethnolinguistic connection; in Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Cyprus, it has made military interventions; and in Syria, it has capitalized on the religious element to back the new regime that ousted Bashar al-Assad.

India’s approach to the South Caucasus is constructive and balanced. The country has developed defense cooperation with Armenia, exemplified by significant arms deals while maintaining substantial economic engagements with Azerbaijan and Georgia. However, further regional instability could jeopardize Indian connectivity projects, in which Iran plays an important role. A potential countermeasure is establishing a multilateral framework that includes the countries involved in the connectivity projects, including the South Caucasus, Iran, and India, to foster regional stability and secure emerging trade routes.

Dr. Sergei Melkonian, Research Fellow at the Applied Policy Research Institute of Armenia (APRI Armenia), Armenia

Captain Alok Bansal, Executive Director of South Asian Institute for Strategic Affairs (SAISA), India

(The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the IPIS)

Bio

Dr. Sergei Melkonian is a Research Fellow at APRI Armenia, focusing on Russia and Iran. He is also a visiting professor at Yerevan State University and Russian-Armenian University. Before joining APRI, he served as an Assistant to the President of Armenia from 2020 to 2022, covering post-Soviet countries and the Middle East. Dr. Melkonian was a Research Fellow in the Institute of Oriental Studies (RAS) for four years, focusing on Israeli foreign and defense policy, as well as security dynamics in the Middle East. From 2018-2020, he was Head of the Eurasian and Middle Eastern Department at the Armenian Research and Development Institute. He holds a PhD in History. He has authored multiple academic papers for peer-reviewed journals and written several book chapters, analytical reports, and articles for different think-tanks, as well as op-eds for international platform

Captain Alok Bansal is the Executive Director of South Asian Institute for Strategic Affairs (SAISA). He has been the Executive Director of the National Maritime Foundation (NMF) and has worked with the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) and Center for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) earlier. He has authored a book titled “Balochistan in Turmoil:Pakistan at Cross Roads’; in 2009 and has co-edited several other books. Alok Bansal is the Executive Director of South Asian Institute for Strategic Affairs (SAISA). He has been the Executive Director of the National Maritime Foundation (NMF) and has worked with the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) and Center for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) earlier. He has authored a book titled “Balochistan in Turmoil:Pakistan at Cross Roads’; in 2009 and has co-edited several other books.

[1] The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is a key project for India’s connectivity with the Eurasian heartland. The corridor consists of three main routes: (1) a western branch through Iran and the South Caucasus, (2) a central branch through Iran and the Caspian Sea, and (3) an eastern branch through Iran and Central Asia. All three routes pass through Iran, making it a critical hub for the initiative.